Ingenuity and Intrigue

The World’s Fair

The Victorian Era ushered in a new time of progress. In the 19th century, industrialization created new avenues for imagination. With growing technological advances, people of varying backgrounds could travel, communicate, and consume new goods and ideas more than ever. Nothing exemplified these changes more than the world’s fairs, from the introduction of automobiles and electronic gadgets to brownies and Dr. Pepper.

A world’s fair is “a large international exhibition designed to showcase achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a period of time, ranging usually from three to six months.” [1]

The world’s fairs were extraordinary expositions of Victorian ingenuity, inspiring many new ideas of possibilities in art, technology, and industry for attendees, including the Körners.

While world’s fairs were common in the 19th and early 20th century, with official expositions sometimes occurring in back-to-back years, this virtual exhibit explores the World’s Fairs that impacted the Körner family.

The Great Exhibition

The tradition of the world’s fairs can be traced back to the “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.” The brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, the Great Exhibition was designed as an international exposition, “for the purpose of exhibition of competition and encouragement.” [2]

The American exhibit at the Great Exhibition displayed an eagle holding drapery of the iconic Stars and Stripes.

As a demonstration of industry and growth, the Great Exhibition opened on May 1, 1851, in London’s Hyde Park. As the host, the United Kingdom took advantage of the Great Exhibition to showcase exotic treasures from across the British Empire, which at the time spanned four continents. Likewise, countries from across the world flocked to Britain to set up presentations. The 15,000 contributors displayed over 100,000 objects, including a locomotive engine, electric telegraph, and Colt firearm prototype. Queen Victoria exclaimed that the Great Exhibition had “every conceivable invention.” [3]

Lasting for six months, approximately six million visitors explored the tens of thousands of displays. The Great Exhibition proved successful in bringing together people from all parts of society as well as promoting education and modernization.

The World Cotton Centennial

Following in the footsteps of the Great Exhibition, the world’s fair opened in New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 16, 1884. Highlighting the history of the earliest export of cotton from the United States to England in 1784, the fair was named the “World Cotton Centennial.” At the time, New Orleans was home to the Cotton Exchange, a centralized point for cotton trade, and approximately one-third of all the world’s cotton went through the city.

However, the fair hit major roadblocks from financial complications. The United States Congress lent $1 million to the fair; but the site’s construction encountered scandal and corruption. The state treasurer, Edward Burke, embezzled nearly $1.8 million, most of the fair’s budget, and fled to Europe. The mismanagement led to the fair opening late, and even after opening, exhibits and even buildings were incomplete. Due to bad press, it is estimated that over one million people attended the fair, three million fewer than expected. The fair closed on June 2, 1885, and proved to be a financial disaster for the city, costing the city over $2 million overall. [4]

Mexico spent over $200,000 on a lavish pavilion, known as the Alhambra Palace, which proved a huge success.

Despite its difficulties, the fair had its achievements. Across 249 acres of the Upper City Park (now Audubon Park), the fair was accessible by railway, steamboat, and ship. The fair boasted that the “Main Building is the largest ever erected and covered thirty-three acres of space…Wide and spacious galleries, twenty-three feet high, are reached by twenty elevators supplied with the most approved safety appliances and convenient stairways.” Electric lights, still a novelty at the time, allowed the fair to remain open until nine at night. Twenty-seven countries and three colonies participated, with countries setting up their own pavilions (think: Disney’s EPCOT). [5]

In 1884, Jule Körner worked for W.T. Blackwell & Co., the famous tobacco manufacturer based out of Durham, North Carolina, that would go on to produce Bull Durham Tobacco. As the manager of the advertising department, Jule earned recognition for the creation of the Bull Durham outdoor advertising campaign, painting large renderings of bulls on billboards or sides of buildings. With the distinctive branding and advertising repetition, this marketing helped Blackwell and the Duke Family become extremely successful. [6]

For the World’s Cotton Centennial, Jule designed and constructed prize-winning exhibits for Blackwell & Co. in New Orleans. [7] Their display was located in the Main Building in the Raw and Manufactured Products, Ores, Minerals and Woods group. This classification included products of hunting, shooting, fishing, chemical and pharmaceutical products, leather and skins, and more. In the official catalogue of the 1884 New Orleans World’s Fair, they advertised first grade long cut smoking tobacco, second grade long smoking tobacco, and cigarettes.

As a souvenir, Jule Körner purchased a Victorian dressing-case from the French Pavilion at the world’s fair as an engagement gift to Polly Alice Masten in 1884. The two were wed in 1886.

As the ability to travel for extended visits, to see relatives or friends increased, dressing-cases became popular among affluent women in the Victorian Era. Owners would often prominently place their cases on the dressing table to demonstrate their style and wealth. [8]

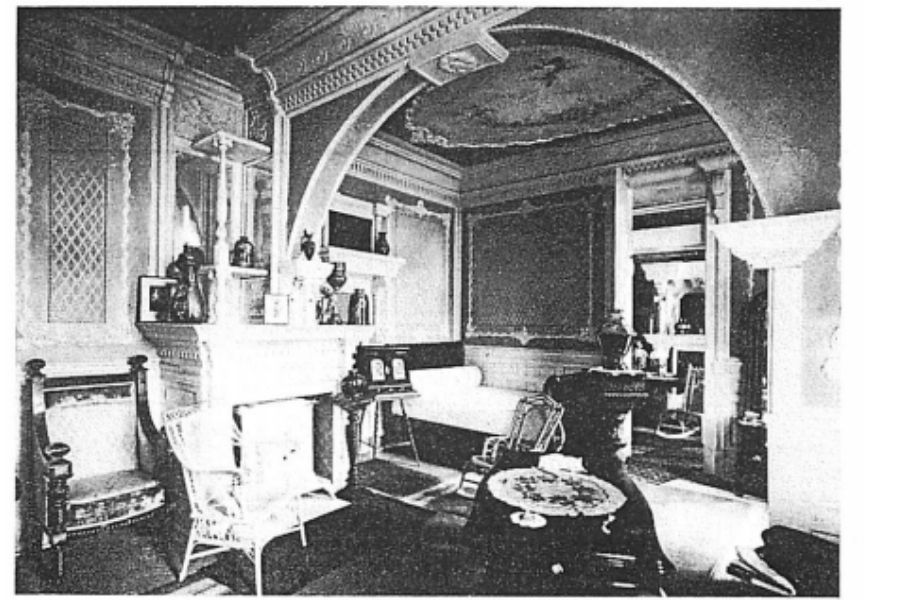

In the historical photo on the right, the dressing-case that Jule brought back for his fiancé from New Orleans can be seen on display next to the bed in the Master Bedroom. Polly Alice’s dressing-case was passed down to her female descendants and is now on view in the Dressing Room of Körner’s Folly, on loan from Polly Alice’s great-grandaughter, Patricia Wolfe Peeler.

Peek Inside!

The World’s Columbian Exposition

President Grover Cleveland delivering his speech to open the Chicago World Fair in 1893.

On May 1, 1893, in Chicago, Illinois, President Grover Cleveland illuminated the iconic World’s Columbian Exposition with a single touch of a button. He spoke to the crowd, “As by a touch the machinery that gives life to this vast Exposition is set in motion, so at the same instant let our hopes and aspirations awaken forces which in all time to come shall influence the welfare, the dignity and the freedom of mankind.” [9]

President Grover Cleveland is said to have unnecessarily punched the button with his fist so hard that he nearly broke it.

Literally, the gold-and-ivory telegraph key ignited a 2,000-horsepower steam engine in Machinery Hall that lit the fairground. More symbolically, as the first fair powered by widespread electricity, it served as a reflection of urbanization’s future, introducing the groundbreaking invention to the average American. [10]

In the midst of the Gilded Age, Chicago bid fiercely for the opportunity to host the exposition. Thanks to its central location and transportation system, Chicago beat out New York City, Washington D.C., and St. Louis to host the World’s Columbian Exposition, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the New World in 1492. In total, 46 countries participated in the fair, complete with exhibition halls, amusement parks, and incredible architectural feats. [11]

Architect Daniel H. Burnham, designer Charles B. Atwood, and famed landscaper, Frederick Law Olmsted designed the 690 acres in Jackson Park with canals, lagoons, and temporary buildings in a white, decorative Neo-Classical façade.

Most of the buildings of the fair were designed in the neoclassical architecture style. The area at the Court of Honor was known as The White City. Façades were made not of stone, but of a mixture of plaster, cement, and jute fiber called staff, which was painted white, giving the buildings their “gleam.” Architecture critics derided the structures as “decorated sheds.” The buildings were clad in white stucco, which, in comparison to the tenements of Chicago, seemed illuminated. It was also called the White City because of the extensive use of street lights, which made the boulevards and buildings usable at night. [12]

The Chicago World’s Fair proved a remarkable success with over 27 million visitors passing through the White City between May and October 1893.

What inventions and attractions might Jule Körner have seen while in Chicago?

Chocolate Brownie

Brownies debuted at the 1893 World’s Fair thanks to Chicago socialite and philanthropist Bertha Palmer. The wife of the Palmer House hotel owner was serving as the Board of Lady Managers for the World’s Fair. The ladies wanted a dessert that they would transport easily in boxed lunches in the Women’s Pavilion. Palmer tasked the hotel’s pastry chef to create a new treat and thus the chocolate brownie was born, topped with walnuts and an apricot glaze. [26]

Wrigley's Juicy Fruit

Chicagoan William Wrigley Jr. used chewing gum as an incentive to sell his Wrigley’s Scouring Soap. With each purchase, customers received two packs of chewing gum. The free gum ended up more popular than the paid product. Wrigley switched his business exclusively to chewing gum and debuted the iconic Juicy Fruit flavor at 1893 World’s Fair and introduced the Wrigley’s Spearmint flavor not long after. [27]

Jule Körner brought home a world’s fair souvenir ruby-red drinking cup. The glass features “Gilmer Kerner Jr., World’s Fair 1893” inscribed on it. It was presumably a gift from Jule to his son, Gilmer, who was around six years old at the time.

For Körner’s Folly, Jule purchased an oriental cabinet and chair set from the Chinese Pavilion. While the chairs were passed down to family members, the cabinet remains on display at Körner’s Folly, the only piece in the Reception Room that is not one of Jule’s designs. Click through the pictures below to see the intricate furniture in the Reception Room in the 1900s and the cabinet in the Folly today.

The following year, in 1894, Jule Körner was thought to have created a reproduction of the great Ferris wheel displayed at the Chicago’s World Fair that advertised Bull Durham tobacco in North Carolina. It was described as “the wheel, its passenger cars brimming with tobacco and its entire surface layered with bright yellow leaves appeared as a revolving circle of fold that dominated the exhibition hall.” [13]

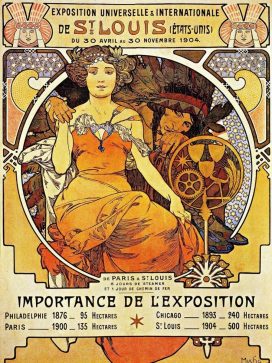

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition

The St. Louis World Fair Exhibition Hall and the Cascades

In April 1904, the world’s fair was held in St. Louis, Missouri, to celebrate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase, the monumental land purchase between the United States and France in 1803. The fair, held in conjunction with the 1904 Summer Olympics, covered 1,272 acres at Forest Park and hosted over 19 million visitors. [14]

As early as April, Gilmer Körner began writing about the fair, stating “When I was home last Mama said that she intends to go this Summer to the St. Louis World’s Fair and that she’d like me to go with her. But Papa expects me to work this summer with Reuben Rink Co and repay some of my expenses this term at [Trinity College, now known as Duke University] I don’t know how it will work out.” [15]

Later that summer, he wrote that he had received a letter that urged all Kappa Sigmas (Gilmer’s fraternity at Trinity College) to attend the Grand Conclave of Kappa Sigma (KE) at the St. Louis fair in August. He noted that the eligible KEs could take advantage of hotel accommodations at the North Fairgrounds at rates of $1.50 per day for a room without a private bath, and $2.50 for a room with a private bath. While Gilmer acknowledged he could not make the Conclave, he wrote that he wished to attend the Fair with his mother, Polly Alice, when she planned on attending in the fall. [16]

Polly Alice left for St. Louis on October 18, 1904. Her husband, Jule, could not attend due to work commitments, so he sent his older brother, Joseph Körner to travel with his wife. She wrote to Gilmer during her trip to update him and the family on her goings, noting the attractions and plays she saw.

While we do not directly know what Polly Alice thought of the world’s fairs, we do know the trip inspired her to dive into her family history, as seen in her memoir, I Remember. “I have always been interested in family history but did not go to work actively on it until 1904, the year of the St. Louis Exposition. After attending the Exposition, I spent 2 weeks visiting in Hendrix County Indiana.” [17]

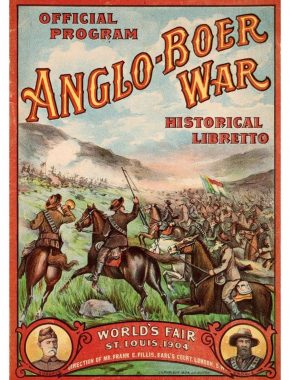

While in St. Louis, Polly Alice wrote to Gilmer to inform him that she and Joseph watched an Anglo-Boer War battle reenactment. The war between the British Empire and two native Boer tribes of Southern Africa resulted in a British victory and over 26,000 Boer civilian deaths in concentration camps. [19]

The battle reenactment Polly Alice and Joseph attended, billed as “the greatest and most realistic spectacle known in the history of the world,” featured the Boer concession to the British. The show took 2-3 hours and grossed over $630,000, with 25 cent ticket admission for bleacher seats and up to one dollar for box seats. [20]

There were 1,500 buildings with exhibits from 62 countries and 43 states. Many of the exhibitions reflected the Victorian obsession with the “exotic:” both foreign goods and ethnic people. While at this point, world’s fairs positively promoted globalism, they also occurred at the height of colonialism and American imperialism.

Anthropological exhibits of indigenous peoples: men, women, and children from around the world, such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico were brought to St. Louis for display. American anthropologists designed the fenced-in exhibitions to imitate their respective native villages, essentially creating a display with real, live indigenous peoples. [18]

Gilmer and his mother missed each other, as Polly Alice left on November 3, 1904, to visit Masten relatives in Indiana, and he arrived in St. Louis on November 8th. There, he stayed at the boarding house of Mrs. E.P. Kistler at 2533 N. Grand Ave, 25 minutes from the fairgrounds. [21]

Gilmer marveled about his first big journey alone, remarking

I am overwhelmed with the grandeur of this world’s fair. The view up & down the main concourse of the grounds. With the grand cascade in the background. Magnificent! I wanted so much to share it with mama. Being here all alone is a novel as well as an exciting experience. I have never been able to make a decision of any independence whatever … All of our life to learn by observation & experience as well as by precept.

What inventions and attractions might Gilmer Körner have seen while in St. Louis?

Historians note that there were numerous parallels between the St. Louis and Chicago World’s Fairs. Most notably, the size and architecture in the 1904 exposition emulated the Beaux-Arts style of the 1893 one. The temporary buildings in Missouri were known as “Ivory City,” a nod to Chicago’s iconic “White City.” [22]

The architecture was not the only familiarity. Gilmer would have even seen the same Ferris wheel that his father did in 1893. Almost ten years after it successfully debuted at the World’s Columbian Exposition, the Ferris wheel was dismantled and sent to St. Louis to wow fairgoers once again. The original Ferris wheel was demolished in 1906; however, its legacy as a carnival staple remains. [23]

Gilmer also brought the world’s fair’s innovation to the Folly. During his visit to the Machinery Building, Gilmer became particularly intrigued by the “Ericson engine,” a pumping engine run by hot air.

He noted: “I was interested because Papa is installing a water system in “Folly”. There is no city waterworks or sewage plant in Kernersville; so it will have to be a private system throughout – and one of the chief problems is how to lift water from our well to a big water tank on the SE deck roof of the Folly. There is at present a “force pump” at our well which is located at NE corner of “Folly”. – but it has to be powered by hand, & the question is whether it will be possible to raise enough water to raise it fast enough, to supply Folly” by such a hand-operated “force pump.” It is very doubtful. There’s no electricity in [Kernersville] so that is out of question.… I got a good deal of literature with pictures etc. to take home. Also gave the man my dad’s address & told him I thought he would be interested- I explained the problem at “folly” and he said that it’s just the sort of situation this “hot-air” engine was designed to meet.”

He noted: “I was interested because Papa is installing a water system in “Folly”. There is no city waterworks or sewage plant in Kernersville; so it will have to be a private system throughout – and one of the chief problems is how to lift water from our well to a big water tank on the SE deck roof of the Folly. There is at present a “force pump” at our well which is located at NE corner of “Folly”. – but it has to be powered by hand, & the question is whether it will be possible to raise enough water to raise it fast enough, to supply Folly” by such a hand-operated “force pump.” It is very doubtful. There’s no electricity in [Kernersville] so that is out of question.… I got a good deal of literature with pictures etc. to take home. Also gave the man my dad’s address & told him I thought he would be interested- I explained the problem at “folly” and he said that it’s just the sort of situation this “hot-air” engine was designed to meet.”

Gilmer updated his diary, noting after returning home he “went over all this with Papa, and as result, there was correspondence with the manufacturer & eventually, a mechanic came and installed this pump at the folly and it remained in action, & was means of “Folly’s” water supply system for some years until town waterworks were installed.” [24]

For 170 years, world’s fairs have shaped the world as we know it today, promoting achievements from all across the globe. With the quintessential Victorian legacies of imperialism, travel, and industrialization, these international expositions brought nations together to celebrate technological breakthroughs and a vision of the future. The Körner family, and in turn, the Folly, participated in, learned from, and benefited from their time exploring.

World’s fairs were an opportunity to show off and debut new products – they speak to the importance of globalization, invention, and more. They were a place to not only bring home just souvenirs but also new ideas. It is unsurprising to think the fairs served as a venue where an innovator like Jule might have felt right at home!

What's next for World's Fairs?

Since the creation of the Bureau of International Expositions in 1928, an organization that oversees international exhibitions, world’s fairs (or now more widely known outside the U.S. as World Expos) are limited to every five years. However, specialized expos, with specific theme, are permitted in the in-between years. The next world’s fair is expected to occur in 2023 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with the theme of “Science, Innovation, Art, and Creativity for Human Development: Creative Industries in Digital Convergence.” [25]

This exhibit was made possible thanks to the generous support from our friends at Robinson & Lawing LLP.

Sources

- Findling, John. “World’s Fair.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., britannica.com/topic/worlds-fair.

- Johnson, Ben. “The Great Exhibition 1851.” Historic UK, Historic UK Ltd, historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Great-Exhibition-of-1851/.

- Picard, Liza. “The Great Exhibition.” The British Library, The British Library, 13 Mar. 2014, www.bl.uk/victorian-britain/articles/the-great-exhibition.

- “NEW ORLEANS, UNITED STATES 1884-5 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition.” America’s Best History, americasbesthistory.com/wfneworleans1884.html.

- Official Catalogue of the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial, 27.

- Körner, Jules Gilmer Jr. Joseph of Kernersville,

- Webb, Mena. Jule Carr: General Without an Army, 144-45.

- “History of the Dressing Case.” Antique Ethos, www.antique-ethos.co.uk/dressing-case..

- “Opening Day, Part 9: President Grover Cleveland’s Address.” Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair, 29 Apr. 2018, worldsfairchicago1893.com/2018/04/30/opening_day_09/.

- “Chicago’s World’s Fair 1893.” The Making of the Modern U.S., Michigan State University , projects.leadr.msu.edu/makingmodernus/exhibits/show/electrifying-america/chicago-s-world-s-fair-1893.

- “The House of Representatives’ Selection of the Location for the 1893 World’s Fair.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives, history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1851-1900/The-House-of-Representatives–selection-of-the-location-for-the-1893-World-s-Fair/

- “Chicago Architecture Center.” Architecture & Design Dictionary | Chicago Architecture Center, www.architecture.org/learn/resources/architecture-dictionary/entry/worlds-columbian-exposition-of-1893/

- Webb, Mena. Jule Carr: General Without an Army, 144-45.

- “All the World’s A Fair.” Explore St. Louis, 4 Sept. 2020, explorestlouis.com/itinerary/all-the-worlds-a-fair/.

- Excerpt from Jule Gilmer Körner Jr.’s 1904 diary.

- Ibid.

- Korner, Polly Alice Masten. I Remember, 9.

- “St. Louis World’s Fair.” Human Zoos, Discovery Institute, humanzoos.org/category/explore/st-louis-worlds-fair/.

- Pretorius, Fransjohan. “History – The Boer Wars.” BBC, BBC, 29 Mar. 2011, www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/boer_wars_01.shtml.

- Excerpt from Jule Gilmer Körner Jr.’s 1904 diary.

- Ibid.

- “Sturctures.” 1904 World’s Fair: Looking Back at Looking Forward, Missouri Historical Society, mohistory.org/exhibitsLegacy/Fair/WF/HTML/Overview/page3.html.

- Malanowski, Jamie. “The Brief History of the Ferris Wheel.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 June 2015, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-ferris-wheel-180955300/.

- Excerpt from Jule Gilmer Körner Jr.’s 1904 diary.

- “EXPO 2023, 4 Dec. 2019, en.expo2023argentina.com.ar

- “Bertha Palmer’s Chocolate Brownie: The Hidden Gem of Chicago.” Loop Chicago, loopchicago.com/in-the-loop/bertha-palmers-chocolate-brownie-the-hidden-gem-of-chicago/

- “New Products and Technologies.” Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 – the Columbian Exposition, chicagoworldsfair1893.weebly.com/new-products-and-technologies.html.

- “History and Timeline.” Dr Pepper, drpepper.com/en/history.

- “St. Louis, Missouri, Home of the First Ice Cream Cone,” Library of Congress, americaslibrary.gov/es/mo/es_mo_cone_1.html.

- “X-Rays, ‘Fax Machines’ and Ice Cream Cones Debut at 1904 World’s Fair: The Source: Washington University in St. Louis.” The Source, Washington University in St. Louis, 30 Nov. 2020, source.wustl.edu/2004/04/xrays-fax-machines-and-ice-cream-cones-debut-at-1904-world-fair/