Collection Close Up

Looking for a deeper dive into history on your virtual field trip? Körner’s Folly is home to hundreds of Jule Körner’s original furnishings, paintings, and objects. We are fortunate that Jule designed the Folly’s furnishings on such a grand scale — without the benefit of their sheer size, many pieces might have been lost to time during the house’s many repurposes and various occupants — that most of the large pieces of furniture are too big to remove from the house! Today, an estimated 90% of the furnishings in the house are original, and add to our understanding of Jule’s design process, aesthetic, and the needs and wants of the typical upper-middle-class Victorian estate.

The Körner’s Folly Foundation collects, preserves, and interprets artifacts and materials pertaining to Körner’s Folly, the Körner family, and Kernersville’s history for visitors to understand and appreciate today’s town through a knowledge of its past through exhibits, interpretive rooms, and educational programs.

Here we will spotlight a wide variety of items in our historical collection, from the mundane to the extravagant. We believe each object shapes our understanding of what it was like to live in the Piedmont of North Carolina during the Victorian Era.

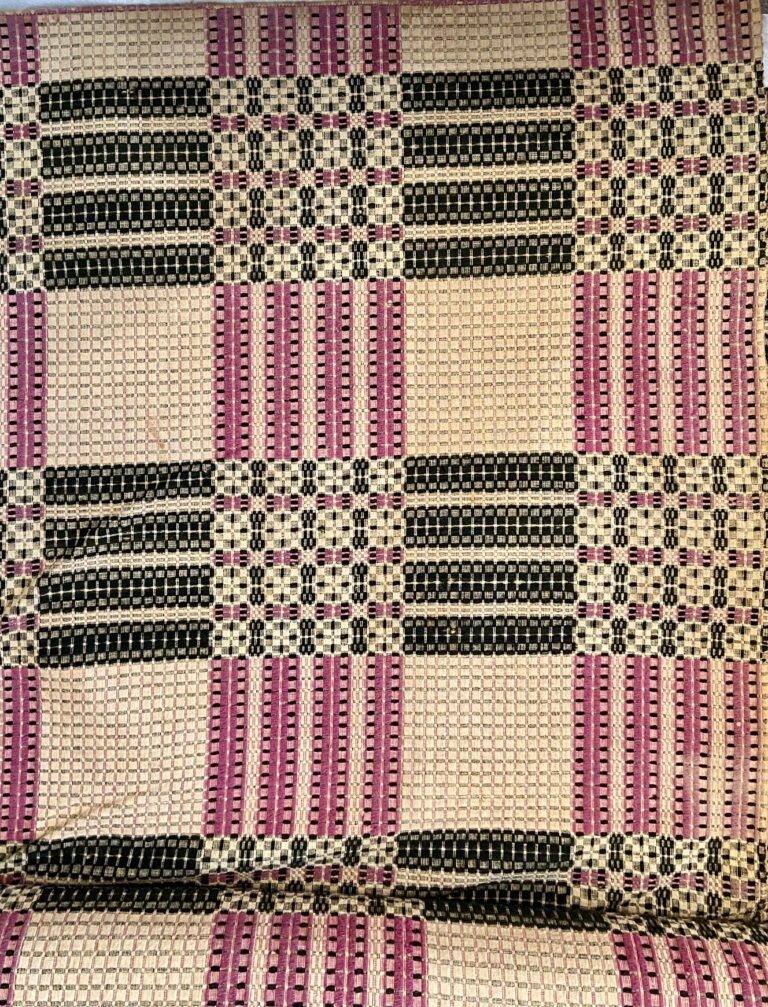

Coverlet

Check out this beautiful, woven coverlet that was passed down through Polly Alice‘s family, the Mastens. It is believed to have been woven between 1835-1845. Coverlets were woven on a loom and usually made of wool and cotton. The wool was generally hand-spun and dyed with natural dyes (purple and black in this case). The cotton was most often machine-spun and left undyed (as seen in the cream sections here). They were used as the top most bed-covering, particularly to add another layer of decoration and extra warmth in the colder months of the year. Designs were often repeating geometric patterns created by a second or third weft. Specific designs were often handed down through family members and shared within communities like a good recipe.

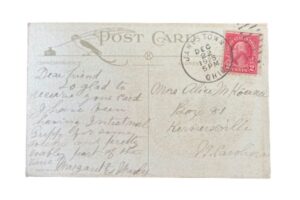

Körner Family Christmas Cards

This collection of Christmas Cards were received by the Körner family in the early 20th century.

Did you know the first Christmas card was sent in 1843? It was created by Henry Cole, who wanted to send his acquaintances something different from his usual Christmas letter. By the late 1800s, advances in printing technology made Christmas cards more readily available, growing in popularity. Early Christmas cards usually contained images of flowers and animals. Collecting and displaying greeting cards became a very popular Victorian pastime.

On Christmas Day 1914, Gilmer Körner remarked that the weather was “cold and disagreeable” but that he received a “great many cards from friends.”

In 1915, the Hall Brothers Company, which later changed its name to Hallmark, printed the first 4 X 6 folded cards inserted into an envelope. This gave people more space (and privacy) to write than traditional postcard style Christmas cards. These became the first “greeting cards” as we know them as today.

Punch-tin Lantern

Aunt Dealy would have used this lantern on her daily walks back and forth between her house and Körner’s Folly, in the dark early morning, and late evening hours.

Lamps made out of tin and punched with holes date back centuries, and were especially popular in the American Colonial Era (late 1700s and early 1800s). They were a practical way to carry lit candles. The holes punched into the lanterns helped display light, and at the same time, the lantern surround kept the flame from being blown out by the wind.

Traditional tin lamps were often made out of recycled metal such as old cans and stovepipes. They were then customized with beautiful and intricate designs made of dots and dashes “punched” into the metal using a hammer and nail. Notice the radial sunburst pattern featured on Aunt Dealy’s lantern. It resembles a sunrise or sunset – the time-of-day Aunt Dealy would have been using this lantern.

Looking for a craft project this winter? You can make your own punch-tin lantern with a few items at home, with the help if an adult. You will need an empty metal can, of any size, like a coffee can or vegetable can, as well as a hammer, nail, and marker. Mark out your designs on your empty can, and then gently tap the nail with the hammer to punch the holes. Be careful – it will be sharp! Then place a small candle in the can, and you now have your own punch-tin lantern!

Witches’ Corner

The European tradition of the “witches’ corner” dates back several centuries. It is said that guests were asked to put a coin in the witches’ pot as they entered the house. This was to attract the attention of bad witches, spirits and ghosts, luring their attention to the coin in the pot. The guest would then be able to enter the house without bringing along any additional unwanted visitors into the home.

At Körner’s Folly, the Witches’ Corner, located on the Front Porch, features a black cast-iron pot that stays mysteriously full of coins. Jule Körner, who designed the house, most likely drew from his heritage and Germanic traditions. His grandfather, Joseph Kerner, immigrated from Furtwangen, in the Black Forest region of Germany in 1785, no doubt bringing many Old World beliefs with him.

Dore’s Seersucker Dress

This beautiful seersucker and lace dress belonged to Dore Körner (1889-1980). The Southern fabric originated in 1907 when a New Orleans merchant set out to design a lighter-weight suit that could withstand the summer heat, humidity, and sweat. The blue and white fabric was born, named “Seersucker” from the Persian for “milk and sugar” in homage to its textured weave.

Cherry Pitter

This 1860’s cast-iron cherry pitter was used in the Kitchen at Körner’s Folly. Aunt Dealy probably relied on this useful tool to help her create one of her signature dishes, a good old-fashioned cherry pie.

During the period between 1840 and 1870, the Industrial Revolution brought about many changes to kitchens. Foundries began making standardized stoves and hearths that made heating and cooking inside easier and safer. Smaller cast-iron implements were also patented and mass-produced, including cherry pitters, apple peelers, lemon juicers, sausage makers, pea shellers, nut crackers, and more. These tools greatly reduced the need for human workers in the kitchen, and because of this, were sometimes themselves referred to as “servants.”

Calling Card Receiver

This butterfly-shaped calling card receiver was made around 1900 out of cast brass. It originally featured colorful enamel as decoration and was made in the Art Nouveau style.

Art Nouveau is French for “new art”, and was a result of a philosophy that merged nature with design. This decorative style became popular in America between 1890 and 1910, and featured curving lines, organic shapes, animals, plants.

The Körner family would have used this butterfly receiver to store cards, letters, or other correspondence. Calling cards in this time period were way of communicating, to express appreciation, offer condolences, or simply to say hello. If the recipient was not home or not receiving visitors, a servant would accept a calling card, placing it in a tray in the foyer. A tray full of calling cards was the Victorian era’s social media, a way to display who was in one’s social circle. Frequently, the cards of the wealthiest or most influential people were left at the top of the stack to impress other visitors. Calling cards and business cards worked in a very similar fashion.

Cane Chair

Have you ever noticed Aunt Dealy’s original chair, located in Aunt Dealy’s cottage? It was made with a special chair caning technique called porch cane or wide-binding cane. Cane or “wicker” weaving dates back centuries. Some of the earliest cane artifacts ever found include a woven daybed that once belonged to King Tutankhamen, (1325 B. C.). Chair seat weaving, and especially chair caning was practiced in South East Asia, Portugal, France, and England in the mid-1600s, becoming very popular and extensively used throughout the world in 1700-1800s and on into the early 1900s.

For this style of porch cane, seats are woven around the seat dowels of chairs and rockers using very wide (1/4″) strips of cane, forming a double layer of weaving with a pocket inside. You can learn more about the history of chair caning and watch someone weave a seat here (weaving starts at the 23 minute mark).