The Körner Family

Meet the Körner Family

In 1878, Jule Körner began constructing what would become Körner’s Folly. As an interior and furniture designer, decorator, and painter, Jule planned to use this building to showcase his design work to his clients. He filled Körner’s Folly with his interior and furniture designs, as a “catalogue” for his clients to view his work. As Körner’s Folly began to take shape, its unique design defied simple description and the house was constantly under renovation to make way for new designs. He married Polly Alice in 1886 and together they had two children – a son Gilmer, and a daughter, Dore. Jule and Polly Alice lived and worked together in the Folly for nearly 40 years.

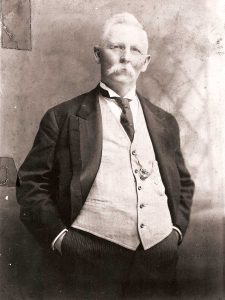

Julius Gilmer Körner — “Jule” (1851 – 1924)

Julius Gilmer Körner

Julius Gilmer Körner was born in 1851 in Kernersville, North Carolina, to local magistrate Philip Kerner and his wife Judith Gardner.

Kernersville was settled by his grandfather, Joseph Kerner, who immigrated in 1785 from Furtwangen in Schwarzwald, a town in the Black Forest region of modern-day Germany. Joseph Kerner eventually accumulated 1,000 acres and started a family in what would one day become the Town of Kernersville.

Jule’s mother, Judith, passed away when he was two years old. He was then raised by Clara, a woman born into slavery who had been purchased by Judith’s father for his daughter when Clara’s previous master died. Jule was said to be a fun-loving child with boundless energy. He was educated at the Kernersville Academy, and upon his graduation in 1865, was sent to a Quaker School in Indiana, where he worked hard and received good grades. Jule loved the arts, especially music, poetry, reading, photography, and painting. However, it was painting that became his passion and he remained in Indiana to study art under William Allen Mote and then advanced art under J.E. Bundy, the noted artist and Civil War photographer.

Jule returned to Kernersville in 1869, and moved into his brother Joseph’s house to set up a studio to paint and practice photography. Clara, known by the nickname “Aunt Dealy,” moved in with the two bachelors and ran the household while they worked and courted young ladies. In early 1873, a railroad line was planned to connect Greensboro with Winston. Kernersville citizens raised money to build a 4-mile section of track to bring the railroad directly through town, and even helped construct it themselves. Joseph left his teaching job and went to work for Western NC Railroad, and he put Jule to work supervising the thirty men building the line.

The following year, Jule traveled to Philadelphia to continue his study of the arts. He carried with him letters of recommendation from his art professors and painters, William Mote and J.E. Bundy, a founding member of the Society of Western Artists, and from leading Quakers from his schooling in Richmond, Indiana. During the next couple of years, he studied design and interior decorating under Charles Fischer and served as his apprentice. Upon receiving the news of his father Philip’s passing in 1875, Jule returned to Kernersville. From Kernersville, Jule began a sign painting business, and worked for businesses in Kernersville, Winston, High Point, and beyond.

In 1877, he began designing what would become Körner’s Folly. Construction began in 1878 on his combination studio, office, and home, and was completed in 1880. With Körner’s Folly complete, he started the Reuben Rink Decorating and House Furnishing Company, using Körner’s Folly as a living catalog for his interior decorating busiess. A year later, his unique home and sign painting business was starting to gain regional attention. Julian S. Carr, head of advertising for Blackwell’s Bull Durham Tobacco Co. in Durham, NC, hired Jule, tasking him with making Bull Durham tobacco the best-known tobacco in America. Jule began designing and painting large-scale advertisements featuring realistic bulls on barns, buildings, and boulders, signing them “Reuben Rink” as his nom de brosse, or brush name.

On October 14, 1886, Jule married Polly Alice Masten of Winston, and in 1887, she gave birth to their son, Gilmer. By this time, Jule’s enormous Bull Durham tobacco advertisements were visible throughout the South, widely discussed, and immensely popular. Tobacco magnate Julian Carr promoted Jule to manager of Blackwell’s advertising department and gave him an unlimited expense account. Jule hired four additional crews to paint his signs all over the United States, and eventually their popularity led to what is believed to be the first successful outdoor advertising campaign in America.

In 1888, Carr hired Jule and the Reuben Rink Co. to paint frescoes on the ceilings of his mansion, Somerset Villa, in Durham, NC. Jule was also commissioned to work on several notable properties in nearby Hillsborough, NC, such as Carr’s Occoneechee Farmhouse, the Colonial Inn, and the Inn at Teardrops.

Meanwhile, Jule continued to oversee his crews painting Bull Durham signs. In late 1888, Blackwell’s Bull Durham Tobacco Co. was purchased by W. Duke & Sons – a major step in the formation of the American Tobacco Company, headed by James Buchanan “Buck” Duke. After forming the American Tobacco Company, Buck Duke relocated the company’s headquarters to New York, promising each of the department heads would become a “millionaire.” However, no amount of money or flattery could convince Jule to leave Kernersville and his beloved Körner’s Folly, and in response he quoted the Hindu proverb saying, “Better is one’s own path, though imperfect, than the path of another well-made.”

In September of 1889, Jule and Polly Alice had another child – a daughter, Doré. By 1891, the Reuben Rink Decorating and House Furnishing Company was flourishing, decorating prominent theatres, churches, auditoriums, colleges, and mansions of the southern United States. As his business became more successful it handled larger projects, including the 1892 renovation and decorating of the Kernersville Moravian Church with the help of Caesar Milch, German fresco artist, and his brothers, Joseph, and Henry Clay Körner (who came to be known as Little Reuben Rink).

Jule was, by many accounts, a devoted husband, an indulgent father, and generous to his family and the townspeople of Kernersville. He was also known as a stylish dresser, a perfectionist, and a great salesman. However, he was also described sometimes as quick tempered, headstrong, willful, or exacting. Most people called him eccentric, and many considered him a creative genius.

Polly Alice Masten Körner (1858 – 1934)

Polly Alice Masten Körner

Polly Alice Masten, “Alice” to friends and family, was born in 1858, the daughter of the Stokes County (now Forsyth County) Sheriff Mathias Masten. She was privately schooled on the Masten plantation in Winston, NC. She enjoyed a five-year, mostly long distance, courtship with Jule Körner before they married in October 1886. Alice was twenty-eight, and Jule was thirty-five. They enjoyed many common interests – particularly the love of the arts.

Alice was an energetic and adventuresome young woman. A friend once described her as “a determined cyclone when doing what she loved.” One pastime she enjoyed was riding horses, and she and Jule often rode together, when Alice was healthy enough to do so. The first few years of their marriage were marked by difficulty as Alice contracted typhoid fever right before giving birth to her first child, Gilmer. She recuperated and continued riding, but suffered a minor fall. The following year, Alice gave birth to her second child, Doré. Determined to return to riding, Alice busied herself with renovations to the house and taking care of her young family, and gradually built up her strength to return to the saddle.

Whenever possible, Alice and Jule took it upon themselves to share their love for the arts with the Kernersville community. In 1894, they co-founded the Kernersville Orchestra. Then Alice, with Jule’s support, created The Juvenile Lyceum, a dramatics organization for children seven to thirteen years old, building upon their natural acting abilities and imaginations. The first meeting took place on April 3, 1896 in what is now the Reception Room of Körner’s Folly. For two years, Alice wrote and directed plays, helped children memorize recitations, made costumes, and directed the rehearsals for the productions performed in Körner’s Folly’s long room. She even learned to play the cello so she could perform with the orchestra.

In the autumn of 1896, Alice had a second, more serious riding accident with a painful recovery, worsened by repercussions from the typhoid fever, which plagued her with ill-health for the rest of her life. But Alice persevered. In 1897, Jule designed and built Cupid’s Park Theatre on the top floor of the Folly, and Alice moved rehearsals and performances upstairs. It’s known to be the “First Private Little Theatre in America.”

Alice was a very active hostess and pillar of community involvement as the founder of the Women’s Club of Kernersville, the Kernersville Embroidery Club, and co-founder of the Kernersville Moravian Church What-So-Ever Circle. She enjoyed meeting with fellow members of the Joseph Winston Chapter of the D.A.R. and the Needlework Guild of America. Alice was the glue that held the Körner family together, especially when Jule was away from home, which was often. Alice was dearly loved by Jule, her two children, and the people of Kernersville. The town lost a leading light and cultural mentor upon Polly Alice’s death in 1934, almost ten years to the day after her beloved husband, Jule, passed away.

For further reading about Polly Alice, visit the virtual exhibit, “The Intersection of Music, Arts, and Theatre: A 120 Year Legacy.”

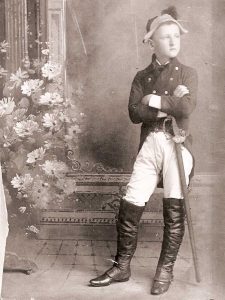

Jule Gilmer Körner, Jr. — “Gilmer” (1887 – 1967)

Gilmer Körner, in costume as Napoleon

Jule Gilmer Körner, Jr. was born in 1887 and went by Gilmer. He was privately schooled in Körner’s Folly where his mother and father encouraged his artistic and musical talents. Like most children of the era, his playtime was minimal, and instead, Gilmer’s studies, art lessons, violin lessons, daily piano practice, Juvenile Lyceum, and the Moravian Church, took precedence. Gilmer also pitched in with household chores, including bringing in wood for the stoves and cleaning, trimming, and refilling over 40 kerosene lamps found through Körner’s Folly. Nevertheless, Gilmer found time to ride horses, go for sleigh rides, and pick fruit in the family orchard. He and Doré adopted a raccoon cub, whom they named Bob. Körner’s Folly was always a revolving door of visitors, with Gilmer and Dore’s frequently coming by to ask Alice for help with their Juvenile Lyceum assignments. There was rarely a dull moment at Körner’s Folly.

When Gilmer was a young man, he was described as compassionate and fun-loving, but also reserved. He attended Guilford College for two years then transferred to Trinity College, now Duke University. He briefly left college to work for his father’s interior decorating business but returned to school, and graduated from Trinity and the Southern Conservatory of Music in 1908. He also received his master’s degree from Trinity College. In 1911, he attended Harvard University, received his law school certificate, passed the bar exam, and practiced law in Winston-Salem at the L. M. Swink law firm.

In 1917, Gilmer enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve, married Susan Brown, and received a commission as Ensign. The newlyweds moved to Washington, D.C. where he worked as Assistant General Counsel to David H. Blair in the Bureau of Internal Revenue. After Susan gave birth to their son Jule Gilmer Körner, III, Gilmer was appointed Commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve, where he served until 1921, when President Coolidge appointed him judge to the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals (now the U.S. Tax Court). Gilmer was elected chief and when he eventually resigned, he resumed practicing law in the Federal Courts, as well as the United States Supreme Court. In 1927, he created a law firm with his colleague David H. Blair in Washington, D.C., called Blair, Körner, Doyle, & Worth, specializing as a corporate tax lawyer. Although Gilmer had the opportunity to start a branch of this firm in North Carolina, he chose to stay close to his grandchildren and never returned home to live in Kernersville.

Gilmer was an avid writer, keeping diaries throughout his life. He also collected artwork and was particularly fond of German and Dutch masters. The 14 paintings displayed at Körner’s Folly today were collected by Gilmer throughout his life. Genealogy was another fascination of Gilmer’s. He meticulously researched and wrote the complete Kerner family story in his book titled, Joseph of Kernersville, in 1958.

Allie Doré Körner – “Doré” (1889 – 1980)

Allie Dore Körner in 1900, age 11

Allie Doré Körner was born in 1889, and like her brother, Gilmer, she was privately schooled at Körner’s Folly. Also like her brother, she went by her middle name, Doré. She was artistic, with a sweet disposition, and was described as an obedient daughter and loving sister. Unlike Gilmer, she was very theatrical, vivacious, confident, and outgoing. Most of her time was spent on school lessons, sketching, painting, piano and cello lessons and practice, the Juvenile Lyceum, and the Kernersville Moravian Church. Doré also found time for her love of animals – especially cats – and at one time had more than thirteen living in Körner’s Folly, who would run around with Bob the raccoon.

Doré attended Guilford College, graduating in 1906, and then attended Salem College, the oldest continually operating educational institution for women in America. She was popular at school, involved in the college’s sorority, and served as yearbook editor. Doré and Gilmer both graduated in 1908 and celebrated by hosting a week-long house party at Körner’s Folly, which was the talk of the town for some time. Jule reportedly spent $15,000 in renovations to get Körner’s Folly ready for this graduation party. She spent the next three years as a socialite and active member of the community, often attending weekend and week-long house parties, card and automobile parties, local club meetings, and community picnics. Doré also traveled throughout the southeastern United States, visiting recreational resorts, hot springs, and hotels. She was courted by many suitors, several of whom proposed marriage. However, Doré was not yet ready for commitment.

In November 1911, Doré boarded a ship by herself in New York City, sailed to France, studied art in Paris, located the Körner family relatives in Germany, and traveled to thirteen additional countries – all of which was highly unusual for a single woman at that time. While she was abroad and after her return in 1913 (the year the cities of Winston and Salem officially joined as one), she wrote articles about her travels for the Winston-Salem Twin-City Sentinel and gave lectures to groups about her experiences. Then, in 1916, she married Drewry Lanier Donnell, Sr. of Oak Ridge, NC, giving birth to their son Drewry Lanier Donnell Jr. in 1919 and to their daughter Polly Doré Körner Donnell in 1923.

Doré was a member of the Historical Book Club of NC, the NC Society for the Preservation of Antiquities, and the NC Literary and Historical Association. She taught adult Sunday school classes at the Oak Ridge United Methodist Church, and was a member of the Guilford County Welfare Board. She was active in the Joseph Kerner Chapter of the D.A.R. and the Federation of Women’s Clubs. She and “Lan” lived in Oak Ridge and chaired the Oak Ridge Horse Show. She and her brother, Gilmer, co-edited I Remember, an autobiographical book of stories written by their mother. She also collaborated on Gilmer’s 1958 book, Joseph of Kernersville.

After the passing of her parents, Doré and her family enjoyed Körner’s Folly as a summer home for many years. As time went on, the costs of upkeep, cleaning, heating, and maintaining the home became too burdensome, and they tried imaginative ways to preserve the home – renting it out to a local architect, renting it as an antique shop, and then eventually, it sat vacant until local families came together to purchase the Kernersville landmark.

For further reading about Doré, visit the virtual exhibit, “Doré Körner: Adventurer, Genealogist, and Journalist.”

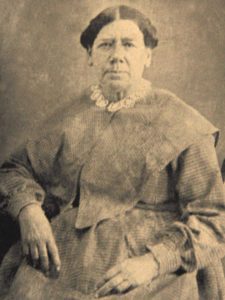

Clara Körner – “Aunt Dealy” (1820 – 1896)

Clara Körner, known as Aunt Dealy

Clara was born in 1820 to Charity, an enslaved woman on the Kinamon Plantation in southeast Kernersville. She worked with her mother and two sisters, Mary and Ailse. When Clara was fourteen years old, Jule’s mother, Judith, asked her husband to hire a daily maid to help with cooking, cleaning, and laundry. She was hired from the Kinamon Plantation to the Kerner family.

When Clara’s owner, John Kinamon, passed away, Clara, her mother, and her two sisters were to be sold at public auction. According to family sources, desperately wanting to avoid her family being separated or sold deeper South, Clara’s mother began quietly asking the Kernersville community for help. She convinced group of Quakers to pool their money and purchase Clara’s sister Mary, who then escaped to Philadelphia with their help. What became of Clara’s sister Ailse is unknown. Jule’s mother and father, Judith and Philip Kerner purchased Clara. Sadly, Clara’s could not avoid a worse fate for herself, and was sold to slave traders who took her further south. Clara and her sisters spent one last night with their mother and never saw one another again.

Clara was described as having light, copper-colored skin, straight black hair, and strong Native American features. Family accounts detail her as intelligent, kind, and industrious with a gentle nature and the natural instincts of a nurse. She became a kitchen helper, cook, and then housekeeper; and took care of the Kerner homeplace.

In 1853, Jule’s mother, Judith, died when he was only two years old. Clara became a stand-in mother figure to Jule, raising him, along with his four other siblings still living at the home. She often called the Kerner children “dearie,” as a term of affection. One of the children had difficulty pronouncing “dearie” and began calling her “dealie.” Eventually all the children (and everyone else) called her Aunt Dealy. The entire Kerner family loved Aunt Dealy, but Jule grew especially attached to her and always considered her his second mother. According to family lore, she spoiled him exceedingly.

Ten years after Jule’s mother died, his father remarried a woman named Sarah Gibbons, and the couple had two sons. Jule was sent to school in Indiana at the end of the Civil War. By the time Jule returned home, his father had passed away. Jule moved in with his brother Joseph, and Aunt Dealy moved in with the two young bachelors. She cooked, cleaned, and watched over them. Once Jule built Körner’s Folly, she moved there and helped Jule keep the house in order and well-provisioned. In 1885, Jule built a cottage behind Körner’s Folly especially for her with the same fine attention to detail he used in the Folly. Aunt Dealy lived there and continued to take care of him, Polly Alice, and their two children – Gilmer and Doré, until her death. Aunt Dealy’s Cottage is still standing on the property today.

Aunt Dealy never married nor did she did have any children, but she did maintain a connection with her relatives over the years. She once received a surprise visit from her long-lost nephew. According to Jule’s writings, a well-dressed man appeared at the Kernersville Depot one day and found his way to Körner’s Folly. Upon his arrival, he announced that he was Aunt Dealy’s nephew, the son of her sister Mary. Mary, also being very fair-skinned, had been able to “cross over” and live as a white woman in the free state of Pennsylvania. She married a white man, a Pennsylvanian business owner, and had one son, who was overjoyed to meet his aunt. After their visit, Aunt Dealy kept a photo of her nephew and his wife in her apron pocket until her passing.

For an African American woman in the nineteenth century, Aunt Dealy was offered several unique privileges. When Philip Kerner passed on in 1875, he left her rental property and a tenant house in Winston, North Carolina. As a property owner, Aunt Dealy earned money by renting the buildings. She was also known to be a talented weaver, once described in a letter as having made from the loom in she had in her cottage “$12 in gold for enough material for a suit of clothes; and that she was saving all of it.”

After being with the Körner family for over fifty-three years – eight years longer than Jule had been alive, Aunt Dealy died in 1896 at the age of 76 years old. An announcement of her death was published in the Twin-City Sentinel. Her funeral service was performed on the North lawn of Körner’s Folly, conducted by both a black minister and a white minister, an unusual occurrence during that period. A large crowd attended. Jule had planned to bury her in the Moravian Church graveyard with other Körner family members, but the church denied his request because the cemetery’s policy of segregation. Jule came up with a solution: he purchased a piece of land adjoining the Moravian graveyard, buried Aunt Dealy near the entrance of the private Körner family plot, and placed a headstone on her grave. About a year after she was laid to rest, Jule built a brick wall around the plot, which can still be seen today.

Her headstone inscription reads:

“Clara Körner

Honest and faithful to every trust

by the loss of our mother at an early age,

she assumed the special care and training of we the children of Philip Kerner

for which we all place this stone to her memory.”

For further reading about Clara, visit the virtual exhibit, “Who Was Aunt Dealy?”

The Körner Family Today

Today, there are still living Körner and Kerner descendants in Kernersville, Oak Ridge, throughout the United States, and living in Germany. Most closely related to Jule and Polly Alice are the children, grandchildren, and now, great-grandchildren of Gilmer and Doré. These descendants were instrumental in saving the Folly from demolition in the 1970s, as well as helping to restore it today.

Friendly Kerner and Körner faces are often seen visiting Körner’s Folly for events, tours, and programs. For more about family genealogy, check out Joseph of Kernersville in the Folly’s Gift Shop or at your local library.